Excessive growth in the number of scientific publications

In this post, Benoît Pier (CNRS Research Director at the Laboratory of Fluid Mechanics and Acoustics – LMFA) and Laurent Romary (Research Director, Inria) write about the recent increase in the number of scientific publications and its effect on scientific research, based on the analysis made in the ‘preprint’ published on arXiv :

“Hanson, M. A., Barreiro, P. G., Crosetto, P., & Brockington, D. (2023). The strain on scientific publishing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.15884. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.15884”.

A study published in arXiv, entitled “The strain on scientific publishing“, addresses the explosion in the number of scientific publications and tries to document this phenomenon precisely, by resorting to quantitative data. The aim is to identify the ingredients of this growth and to understand the consequences for research activity, in particular peer review and bibliographic monitoring.

The authors are specialists in bibliometrics and exploit a range of sources for their quantitative analyses: mainly Scopus and Web of Science, but also directly harvesting the web pages of various journals and publishers. The period analysed covers the last ten years, with a particular focus on 2016-2022.

The first result concerns the total number of articles published, which follows very closely an exponential growth (+5.6% per year). Even taking into account the increase in the number of researchers over this period, we can deduce that the time spent on obtaining the results, validating and peer reviewing them has decreased significantly.

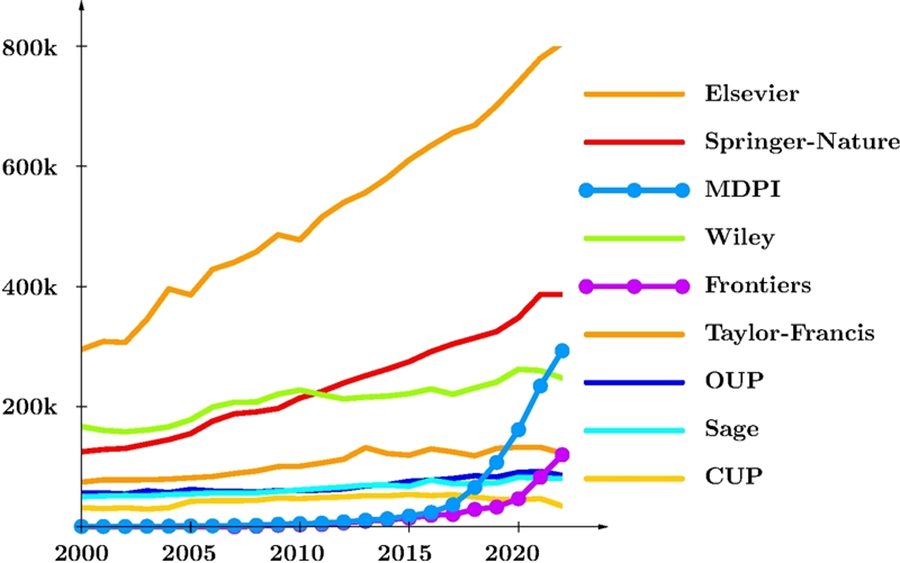

The authors point to a number of factors that could explain this growth, including greater accessibility to scientific publications in the countries of the “Global South”. However, certain factors seem to predominate, and among them, primarily the new editorial practices. By breaking down the annual number of articles by publisher, the authors show that this strong increase is essentially due to a few publishers who have increased their publication volume enormously: MDPI and Frontiers are clearly on very different trajectories compared to most other publishers. By computing the average annual number of articles published per journal, the authors observe that the growth (significant, but not overwhelming) of the traditional publishers is mainly due to the expansion of the number of journals in their catalogues, whereas the very strong growth of Frontiers and MDPI is the result of an explosive increase in the number of articles per journal. It should be noted that these two publishers, which appeared more recently, are thriving through publication fees paid by authors.

To explore this question further, the authors also compared the number of articles published in special issues with those in regular issues. They found that for MDPI, Hindawi and Frontiers, the very strong growth was almost exclusively due to the increase in articles published in special issues – in 2022, the vast majority of these publishers’ articles were published in special issues.

To provide a more detailed characterisation of publication practices, the authors carried out a statistical analysis of the duration of the peer review cycle, i.e. the time from submission to acceptance. These data are not readily available, but the authors were able to harvest them for a sufficient number of articles to obtain statistical distributions by major publisher, and compare their evolution over the years 2016, 2019 and 2022. This statistical analysis shows that, in general, these distributions have hardly changed between 2016 and 2022, and are asymmetrical, with a long tail at long times, corresponding to the “rare events” consisting of articles that are particularly difficult to review. But here again, Frontiers, MDPI and Hindawi display a quite unusual trend r: in 2022, the article turnaround times is much shorter than 2016 and is accompanied by the loss of the long tail. This triad of publishing houses has therefore moved to a much faster and more homogeneous process, while the disciplines covered are quite diverse and the quality of the manuscripts probably just as variable as in the past.

This study highlights two main factors responsible for the explosion in the number of published articles:

- Well established publishers are mainly expanding their catalogues, although there has also been an increase in the number of articles per journal.

- The triad (MDPI, Frontiers, Hindawi) increasingly use special issues to publish more and more articles, and this phenomenon is accompanied by a significant shortening of the time allotted to the peer-review process.

This study has not failed to trigger reactions, particularly from Frontiers in a blog post which disputes the figures, accuses the authors of bias and continues to promote exponential growth. The authors of this study have pointed out that, unlike other publishers, Frontiers did not provide the requested data, and they methodically dismantle Frontiers’ analytical errors in their blog post.

This battle over figures underlines the importance of having accessible and open data in order to carry out this kind of study, according to criteria that guarantee the scientific validity of the results obtained. It is therefore regrettable that this work is largely based on the closed databases of Scopus and the Web of Science. Nevertheless, we have attempted to reproduce certain aspects by querying the open data of the OpenAlex database and we have found exactly the same trends in the number of articles published per year, per journal and per publisher (see the figure below). However, it is not currently possible to carry out exactly the same detailed study using open data.

Let’s hope that the Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information (of which the French Committee for Open Science is a signatory) will facilitate this in the future.

Figure 1: Evolution of the total number of articles published per year and per publisher, data from OpenAlex.

In conclusion, based on the results of this study, we can ask ourselves whether the current system is sustainable. The answer is clearly no. Exponential growth in the number of publications is not compatible with maintaining scientific quality and ensuring confidence in the results, guaranteed by a careful and thorough peer review process. This is all the more true given that the number of members of the scientific community is increasing little, if at all, if we look at the trend in the number of PhD graduates in OECD countries, which, as the authors of the study presented here observe, has been in slight recession since 2018. However, to maintain a high standard, each published article needs to be validated by at least two independent reviewers who can devote sufficient time to this task; and the editorial boards of most scientific journals are having more and more difficulties to find reviewers. If we take the rejection rate into account, we suggest the following golden rule: to maintain a high-quality publication system, each researcher needs to review around ten times as many articles by his or her peers as he or she writes.

Faced with the current inflation in scientific publication, some people are advocating the development of new tools (using “artificial intelligence”, for example) to identify what is relevant, evaluate only worthwhile manuscripts, track down texts that have themselves been generated by machines… But just as with climate change, the deterioration of the scientific publishing system is unlikely to be solved by purely technical means, unless we first rely on human intelligence, aided by a little sobriety.

At the same time, institutions, universities and research organisations, as well as funding agencies, must unambiguously support a reform of evaluation based on the principles of DORA and COARA (see the French chapter of COARA), by banning indicators such as the “h-index” and the “journal impact factor” and encouraging narrative CVs. Publication practices can evolve towards a more virtuous system only if evaluation practices follow the same path.

Rather than to aggravate the current race to publish, it would be better to devote our time to doing better science and therefore to publish fewer and better papers.

Update 13th of November 2024

Since this post was published, the preprint “The strain on scientific publishing” has become a publication and Le Monde has covered the subject. We provide the references below.

- Hanson, Mark A., Pablo Gómez Barreiro, Paolo Crosetto, et Dan Brockington. « The strain on scientific publishing ». Quantitative Science Studies, 8 novembre 2024, 1‑21. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.15884

- « L’inflation du nombre de publications scientifiques interroge ». 12 novembre 2024 – access reserved to subscribers. https://www.lemonde.fr/sciences/article/2024/11/12/l-inflation-du-nombre-de-publications-scientifiques-interroge_6389778_1650684.html