Openness Profile: Modelling research evaluation for open scholarship

Executive Summary

The Openness Profile (OP) will be a digital resource in which a research contributor’s outputs and activities that support openness would be accessible in a single place.

The activities of scholarship go far beyond those typically used in the evaluation events that feed into hiring, promotion, and funding activities. In addition to peer-reviewed journal articles, they may include, but are not limited to: writing or refactoring computer software; developing data management plans; curating data for interoperability; developing infrastructures; and mapping research workflows. Teaching activities, including lectures, course design, curricula and syllabi design, as well as open scholarship training, are also vital contributions to training the next generation of researchers. In this report, we outline the concept of the Openness Profile (OP), which would create a mechanism to improve recognition of, and reward for practising, open scholarship.

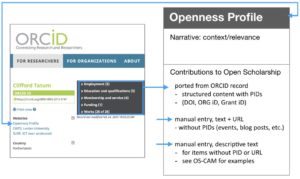

The OP is conceived as a portfolio of contributions to open scholarship curated by the contributors themselves, as described in a presentation by Clifford Tatum at the Openness Profile workshop in July of 2020 [1]. In its initial implementation, the OP would integrate into ORCID as a means to source entries as well as being a part of the ORCID record (see diagram below).

The OP would be embedded in evaluation events conducted by institutions and funders to enable recognition and reward of open scholarship activities, many of which are aligned with the missions of those organisations but are currently invisible or not recognised.

A representation of the OP as a user-curated portfolio of contributions to open scholarship. The OP would include a narrative component to enable the research contributor to contextualise their work as well as contributions drawn from their ORCID record and from the web. Other contributions would be allowed that have no URL as descriptive text.

By extension, open scholarship contributions could be aggregated across groups. Those might be research groups, departments, institutions, private companies or funders. We note that an aggregated profile would require a suitable identifier for groups. These do exist, notably, the RAiD identifier, developed by ARDC, is primarily a project identifier but could also be used for this purpose. However, for reasons of scope and resources, in this report, we focus primarily on the individual openness profile.

The state of open scholarship

A key goal for Knowledge Exchange (KE) is to enable open scholarship by supporting information infrastructure on an international level. KE seeks to support the European research community’s efforts to realise the significant advantages of interconnected, collaborative, and digitally-enabled scholarship.

It is widely recognised that there is a pressing need to accelerate the transition to open, and there have been a number of policy and infrastructure initiatives in recent years aimed at doing so. In addition to KE, and its own Open Scholarship Expert Group, such initiatives include DORA, ACUMEN, LERU, CRediT, THOR, and FREYA, among many others. At the same time, communities of practice have begun developing in both digital and open scholarship, involving researchers, open data experts, technologists, librarians, and others. However, despite this progress, operationalising and normalising open scholarship practices has proven challenging, and progress has been slower than ideal.

The need for collective action

The global academic system is complex, involving many different stakeholders. These include, but are not limited to, national funders, independent funders, national research organisations, academic institutions, commercial research organisations, technology and infrastructure providers, learned societies, commercial publishers, and information companies. Each has their own motives and needs, which can seem to be in immediate conflict with each other. The situation is further complicated by the fact that research is increasingly conducted globally, but is typically funded and assessed based on national and regional strategic objectives.

Conflicting ambitions, combined with strong network effects that punish those who deviate from sector norms around research assessment and practice, make it challenging for individuals and organisations alike to become more open without risking real or perceived negative consequences.

Many of the challenges associated with the transition to open scholarship are economic [2], in that they are either financial or relate to incentives. The difficulty in changing any complex system that is economic in nature is that each actor will tend to behave in a way that most aligns with their own incentives. Systemic change towards openness therefore requires collective action to enable cultural change that shifts these incentives.

Credit where it is due

Significant cultural change is required to create a working system of recognition and reward for contributions to open scholarship. An over-reliance on traditional metrics such as citation counts, and outdated proxies like journal prestige and the Journal Impact Factor, distorts the behaviours of researchers and limits the types of activities that individual contributors can get credit for. In particular, the reliance on published articles to assert provenance creates risk for research contributors that share earlier stage outputs, like datasets and analysis programs.

Career progress is impeded for individuals whose contributions do not conform to that narrow set of characteristics, leading to a loss of talent and lack of diversity of skillsets in academia. As well as being fundamentally unfair, this monoculturalism in turn leads to poor research practices and outcomes due to shortages of critical skills. This works in two directions.

Firstly those research practitioners who are expert in data science, project management, and computer programming tend to leave academia and pursue roles in industry. Secondly, research support personnel within academia are not rewarded for their contributions to research and research outputs. Because their contributions are hidden – they cannot be fully quantified, understood or built upon. If key contributors to the academic knowledge ecosystem continue to be under-recognised, over time there will be a talent-drain towards the commercial knowledge sector.

The first step towards improving the diversity of contributions and contributors that are recognised is to create a shared taxonomy of research contributions and contributors, (such as the CRediT initiative). By making hidden work visible, it is possible to characterise, measure, and reward activities as part of an expanded research evaluation approach.

Investment is needed in the research e-infrastructure

Current research evaluation practices are hindered by overly cumbersome reporting practices that put too much burden on researchers, support staff, and administrators. The result is poor compliance with data entry, poor quality metadata, wasted and duplicated effort, and a degraded evidence base for policy-makers.

Persistent identifiers (PIDs), their associated metadata, and modern IT integrations through APIs are necessary to improve the flow of information between funders, national research organisations, assessors, institutions, publishers, and individual research contributors.

Currently, funder grant information systems are underfunded and underdeveloped. There is poor adoption of PIDs and little to no interoperability with downstream stakeholders. Institutional current research information systems (CRISs)- which are sometimes called research information or research information management systems (RIS/RIMs)- and institutional repositories (IRs) are evolving, with ever-improving interoperability, but there is still much work to be done around standards for information interchange and best practices.

Skills and knowledge gaps

Levels of understanding the need for open scholarship, and what is potentially required to implement it, vary across policy- and decision-makers in funders, institutions and research organisations. More outreach and better education is required to help senior leaders understand the need for change, and the mechanisms that can and should be employed to achieve it.

Within research institutions, there are significant skills gaps at the practitioner level. Greater training is required in reproducibility, data management, computer programming, and open research workflows.

Study to explore the Openness Profile concept

The findings in this report are based on an 18 month study involving interviews, workshops, and focus groups that collectively engaged 80 individuals from 48 different organisations, representing a diverse range of stakeholders from across the research and scholarly communications ecosystem. The project began with a series of 20 semi-structured interviews with key representatives from all stakeholders, the results of which were presented in the report: Openness Profile: Defining the Concepts [3]. Consultation continued in the form of a virtual stakeholder workshop to identify challenges and opportunities involving the OP, and five targeted focus groups where preliminary use cases were identified.

Conclusions

At the end of the report, we present a series of recommendations, firstly for collective action on the next steps required to realise the OP, then specifically for key stakeholders, such as funders, national research organisations, infrastructure providers, and research institutions. These recommendations point towards improvements in education, technical infrastructure and assessment practices.